“Love, Skippy.”

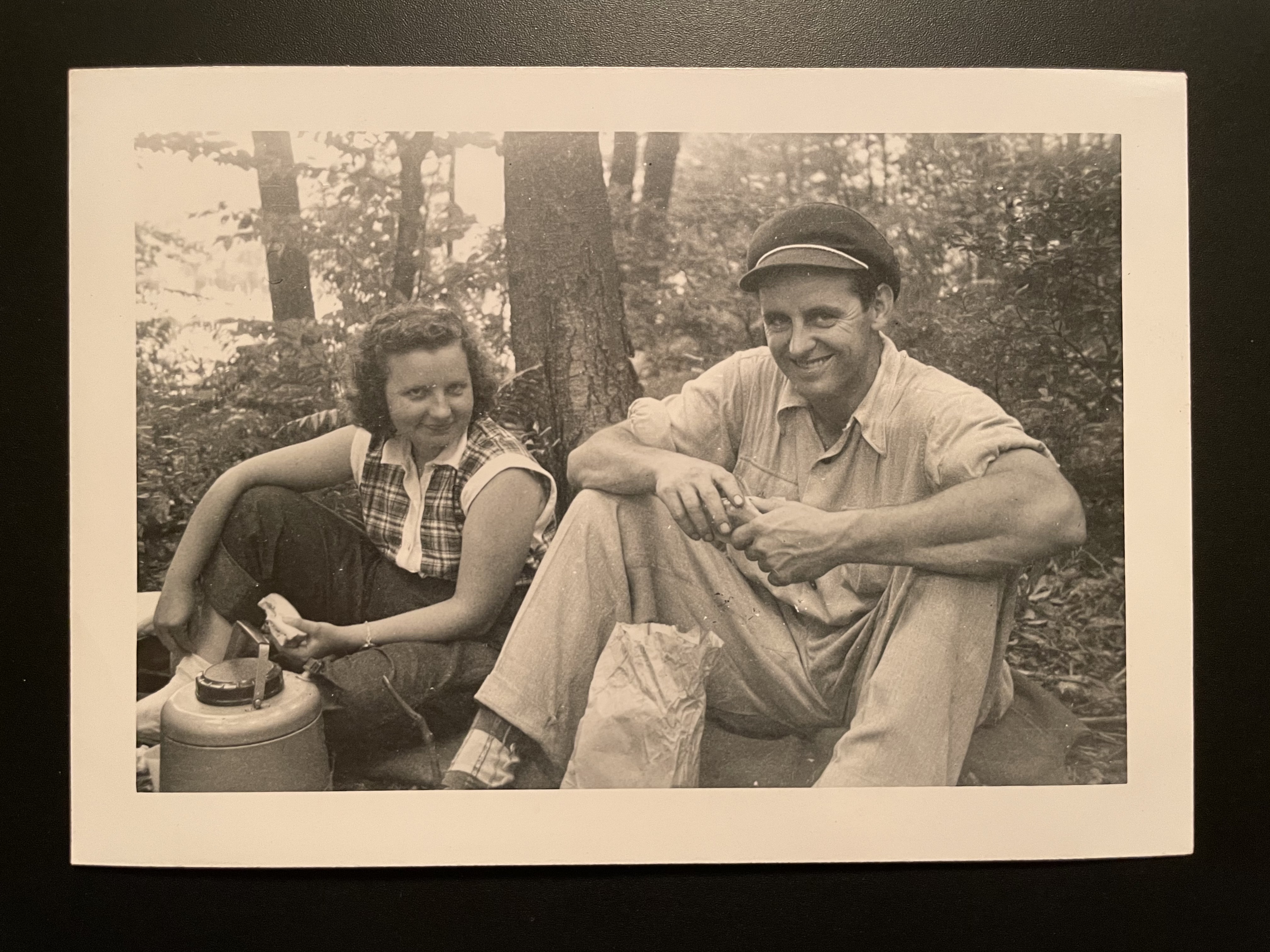

It was signed in an anniversary card that Nan had saved in photo albums I had never seen, before I spent almost every day there with her. I snapped a photo of it almost a year before starting this project. Even then I knew how important it was to document it — to save it for my brain to hold on to when I felt like maybe my memories were fading. The rest of his lettering was mostly on legal pad paper and stuffed in to files in his office. I had written many school notes right next to his over the year I spent on Zoom for school. It was there for me to collect, next to my notes on pixel sizes and parallax code. If I wrote my notes where he wrote his, it felt like he was still close.

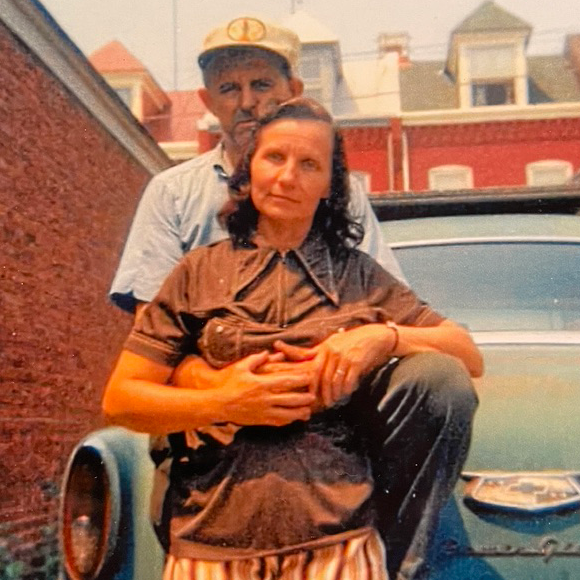

Grammy’s script was also easily recognizable in its arthritic script. Again, I remembered it from holiday cards. I had been stashing those for the last few years just in case. I could remember it visually from grocery lists I might catch a glimpse of at breakfast on a Tuesday or Friday. She would sometimes mix up lowercase and capital letters. My cousin’s photo album was labeled “AshLey.” It made me happy to see. I also do this in my own handwriting.

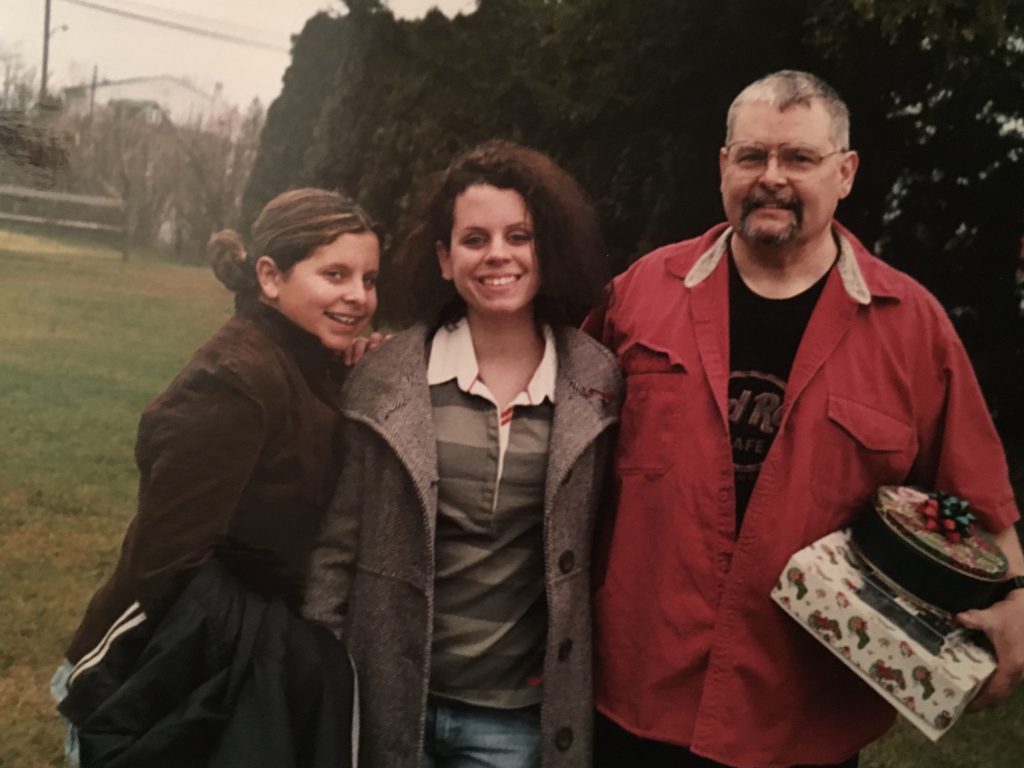

My sister’s handwriting is so different from my own. Her letters are round like my mom’s but short like my dad’s. They’re carefully done, almost methodical. Her notes from school always amazed me. Geometric and precise, friendly and legible. They reminded me of all the cool girls from elementary school. Girls armed with gel pens and highlighters as they copied from the blackboard. I can still remember the letters she would write to me when I was incarcerated. Letterforms with intention. They felt innocent and unhurried, so different from my frantic words written quickly to keep up with my thoughts.